If nutrition feels more complicated than ever, you’re not imagining it. We’re living through one of the most exciting chapters in nutrition science. The discovery of the gut microbiome, the trillions of microbes living inside us, has fundamentally reshaped how we understand the relationship between food and health. It’s opened new doors, new hypotheses and, in many ways, an entirely new language.

But this scientific breakthrough is unfolding in the age of social media. Information (and misinformation) spreads at speed. Advice is shared in seconds. Products are launched before the evidence has caught up. And for many people, it’s becoming harder to know what, or who, to trust. So, let’s take a grounded look at where the science truly stands, what’s genuinely promising, and where we need to slow down.

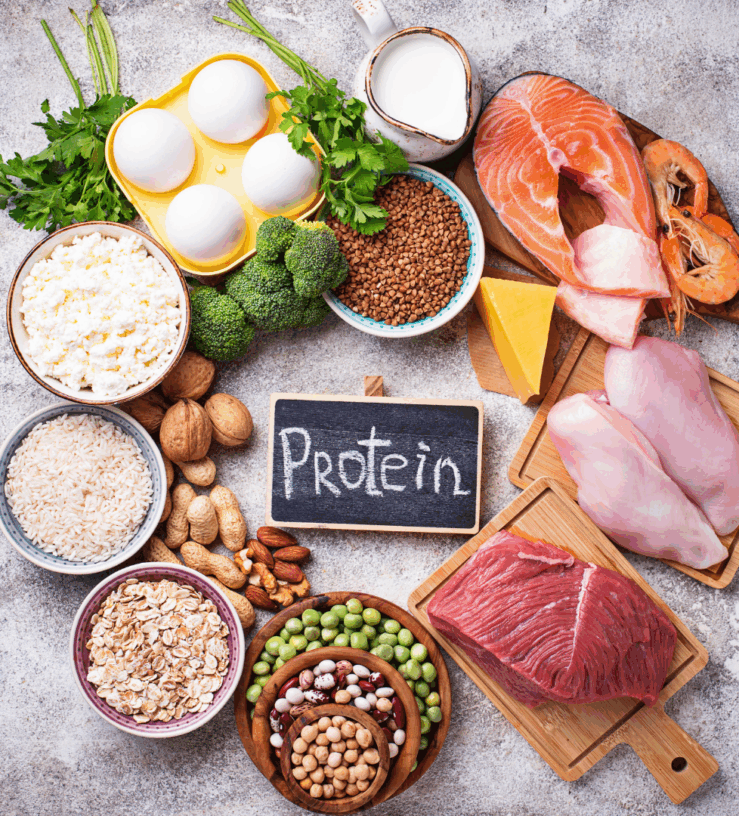

Many nutrition conversations still begin with

Many nutrition conversations still begin with  foods are best for us based on our microbes or blood sugar responses.

foods are best for us based on our microbes or blood sugar responses. While millions of pounds flow into personalised nutrition technologies, the fundamentals of public health nutrition are being left behind. In UK schools,

While millions of pounds flow into personalised nutrition technologies, the fundamentals of public health nutrition are being left behind. In UK schools,