Gut microbiome plasticity

Our gut microbiomes are hugely adaptable, in fact the composition of the microbiome can change a little after every meal. Diet is one of the greatest modifiers of the gut, and we know that fibre from our plant-based foods is the key to creating a diverse and resilient inner ecosystem in our gut microbiome.

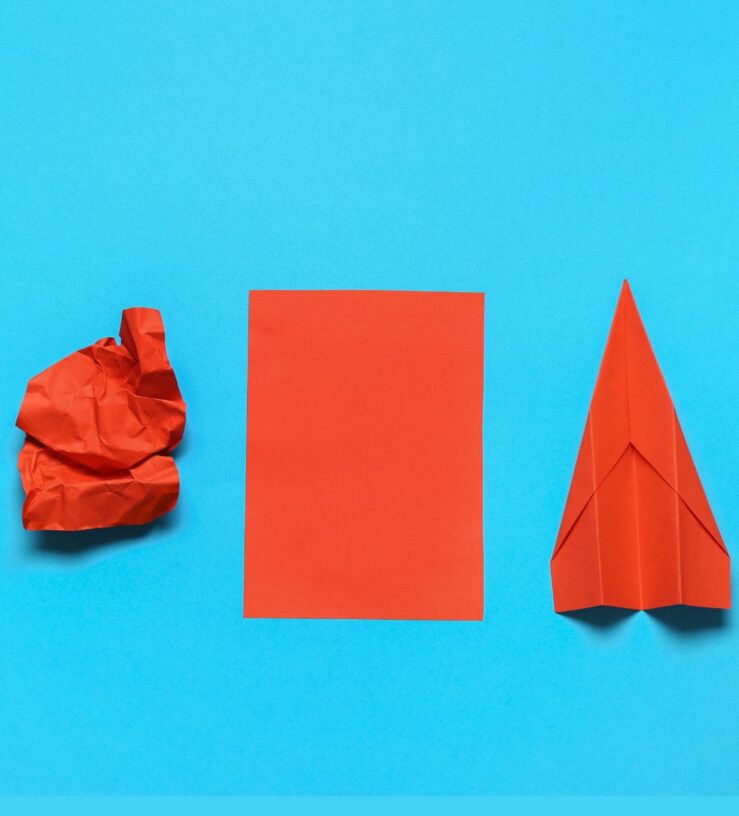

We know fibre is the fuel for a diverse ecosystem, however for many, jumping from a lower fibre diet to a high fibre diet can cause digestive discomfort. We are now understanding that by harnessing the adaptability of the gut, we can train our microbes to develop the enzymes to break down foods like lactose, or legumes. Think of this process as “gut training”.

For example, our recent article on lactose intolerance highlighted it is possible to train the gut to tolerate lactose – especially fermented dairy products like Kefir.

We really commonly hear that legumes (lentils, beans and chickpeas) cause a lot of gas and discomfort, however we know these are key players not only in our gut health, but have wider benefits such as keeping our blood sugars in range at the next meal.

It is also possible to train the gut to tolerate legumes, even on a low FODMAP diet (a medical diet used to relieve digestive discomfort in those with IBS) for example it is possible to still have ¼ cup of chickpeas or lentils each day. To train your gut to tolerate legumes you can start by triple rinsing a can of legumes (chickpeas/beans) and start by introducing ½ – 1 tbsp per person, each day, into the diet. By repeating this small amount, but often, it trains the gut to tolerate this better. Over the weeks you can increase this by 1tbsp increments.

By working with small portions of plant-based foods and having these frequently, the gut microbiome adapts to better tolerate diversity.

Remember – the original study of 10,000 American adults which led to the discovery of gut microbes thriving with plant diversity (30 plants per week) found that adults eating 30 different plants a week have more gut diversity than those who have the same 10 on repeat. This evidence shows that we don’t need to have large portions of fibrous foods to get the benefit, the key is in having smaller portions, more often of a range of plant-based foods to train the gut to tolerate more diversity.

Gut microbiome plasticity – the evidence:

A recent high-quality, multicentre, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled crossover trial titled “Prebiotics improve frailty status in community-dwelling older individuals” provides compelling evidence of the gut’s capacity for adaptation,even in older age. The study recruited 200 older adults (>/65yo), 100 classified as prefrail and 100 as frail, who were randomly assigned to receive either a prebiotic mixture or a placebo for 12 weeks before crossing over to the opposite treatment. This design is particularly robust because both participants and researchers were blinded to which intervention was being administered, reducing bias, while the crossover format meant that each participant served as their own control. Together, these features allowed researchers to confidently attribute observed improvements in frailty status and metabolic function to the prebiotic intervention itself rather than to individual variation or placebo effects. The prebiotic contained a mixture of inulin and oligofructose and the individuals taking the placebo received maltodextrin, all taken after breakfast.

Remarkably, supplementation with a prebiotic mixture for 12 weeks led to measurable improvements in the frailty status of the older adults compared with placebo! Participants showed enhanced muscle strength, walking speed, and grip, as well as reductions in fatigue and constipation. Even more importantly, no GI symptom side effects were reported, except for an improvement in constipation!

Mechanistically, these benefits were linked to the prebiotic action on the gut microbiome and favourable shifts in gut microbial composition and metabolism. The intervention increased beneficial Firmicutes species (such as Lactobacillus and Ruminococcus) and supported the production of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), metabolites produced but our gut microbes that are known to reduce inflammation, improve insulin sensitivity, and maintain muscle metabolism. Conversely, frailty was associated with reduced microbial diversity and enrichment of Bacteroidetes and Proteobacteria, both linked with systemic inflammation and metabolic decline.